I have been inspired to make this effort because of two tremendously moving experiences in the past two days.

Most of you on my address list are more aware of the situation in Palestine and Israel than the American public at large. You are a well-read group, and a few of you have visited this part of the world. Some have been much more closely connected to the situation than have I. And most of you have seen at least some of the photos that our intrepid journalist, Ellen Davidson has been capturing on our trip.

There have been some highly dramatic instances, but to me, the most meaningful experiences have been the quiet revelations of the past two days.

The first of these took place in Ramallah, the administrative home of the Palestinian Authority. The so-called “separation barrier” follows a snaky line intended to incorporate the maximum geographical area into Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries while eventually including the smallest number of Palestinian residents. To achieve this objective, the Israeli government deploys a variety of cruel strategies, many relying on the enforcement of unreasonable, unjust laws. Probably the most common and the most visible is the demolition of homes built or expanded without a construction permit. And since the Israeli government never grants building permits to Palestinians, almost all homes are subject to demolition orders.

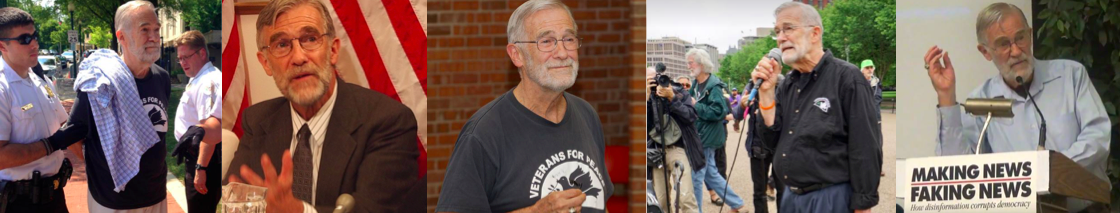

Yesterday afternoon, our Veterans For Peace delegation met with a gentleman who is one of the leaders of the resistance to the wall. He took us to visit one of the areas targeted by the government for “maximum geography, minimum demography” described above. In this neighborhood seven homes and two apartment buildings had been demolished. Demolition crews — caterpillar D9 bulldozers (made in America) protected by police and/or soldiers come in the middle of the night and give residents ten minutes to take what belongs they can carry and vacate the house. In a few hours, there is nothing left but rubble. After viewing several of these houses, our guide took us to a still standing house, adjacent to which was a pile of rubble. He took us into a small garden next to the house, where the owner welcomed us to his home and explained that the rubble behind the house had been a 4-unit apartment building that he had built at a cost of $200,000 to house his sons and their families when they finish their university studies. He then chased his younger children into the house to get glasses and a pitcher of water for his guests. We all sat down to chat with this kindly, gentle victim of Israeli cruelty, and soon coffee, tea, and dishes of fruit, vegetables, and hummus appeared on the table, a miracle of generosity to strangers from a man whose life-savings had been destroyed by a housing demolition order. His residence remained only because it had been built before the 1967 conquest of the West Bank by the Israeli army. For the time being, pre-1967 structures are exempt from demolition orders. I’m sure the taste of the fennel, apples, and oranges we were given in that garden will stay with us all.

Then today we all took the bus ride down to the Negev Desert to visit the Bedouin village of Al Araaqib, one of the dozens of Bedouin villages in the Negev that the Israeli government considers “unrecognized, and therefore ineligible for services such as water, electricity, and trash collection. Nonetheless, the village has been there for centuries as was recognized by the Ottoman Empire in 1905, the British Mandate in 1929, and even Israeli documents in 1975. In June, 2010, the Israeli government demolished the village, destroyed all the houses, bulldozing 4500 olive tree and 900 fruit trees (figs, avocados, lemons and oranges), as well as the water cistern and the electrical generator. Immediately after this disaster, the villages rebuilt the village insofar as the could and credited activist Jewish Israelis with helping them in the revival. But not long thereafter, the government destroyed the reconstructed village. Since 2010, the village has been demolished many more times over the last 7 years. But the steadfast Bedouins persist. Each time their material belongings and surrounding deteriorate further, but the spirit of “sumud” is more powerful than the D9 bulldozers. When we visited Al Araaqib in 2013, they still had a number of travel trailers in the village, one of which served as a computer classroom. The Israeli government destroyed them all. They are poorer than ever, but as hospitable and generous as ever.

As soon as we arrived we were offered tea and water.

Then Aziz, our host started preparing coffee, while telling us how important morning coffee is to the community. He started with raw beans, roasting them in a skillet in which he was continually flipping them while telling of his culture and the attempts of the Israeli government to destroy both their culture and their history. But he started this commentary by saying that the first thing every morning when he wakes up, he raises thanks to God for his life, and then raises thanks to the activist Jews who help the community survive. He teaches his son that he must not hate Jews. He may hate the police, the army, the “green patrols,” and the JNF (Jewish National Fund) — all of which are trying to drive them off the land. But he must not hate the people — or any people.

When the coffee beans were roasted to his satisfaction, his friend Saleem pounded them into power in an iron mortar and pestle. He poured the grounds into a beautiful brass pitcher which had been boiling over a flame while the beans were being pounded. He gently shook the pitcher for a while, the dropped a handful of cardamom branches into the mortar and ground them up, eventually adding a handful of cardamom to the coffee. Finally he poured coffee for us all. Our colleague Mike Haines declared it the “best coffee ever!” We all agreed. It had been made with love.

Then Aziz took us on a tour of the village fields. At one point he grasped a handful leaves from a plant that Mike said was called “mallow” in English. It grows wild in the winter in Al Araaqib and since time immemorial has been one of the staples of the Bedouin winter diet. But the Israeli government has declared it illegal to pick and had made violation subject to an 800 shekel fine (roughly $225 dollars.) He pointed out several more edible wild plants, all enthusiastically tasted by “forager Mike.” Then we were called back to the welcoming tent where a feast of Bedouin dishes had been set out for us. So once again, people from whom nearly everything had been taken were once again giving us loving hospitality so deeply rooted in their culture that it survives monstrous abuse.

After the feast, we joined them in their annual Sunday protest at the Lehavim highway crossing. Then the long bus ride back to Jerusalem.

What amazing human beings these are !!!

Peace,

Ken