By Tim Weiner, May 14, 2020

A crisis of conscience in Vietnam led McGehee to conclude that the agency was “a malevolent force” and to lay it bare in a memoir, “Deadly Deceits.” That memoir of 25 years with the C.I.A. chronicled operations in Southeast Asia and his realization that U.S. efforts in Vietnam were doomed.

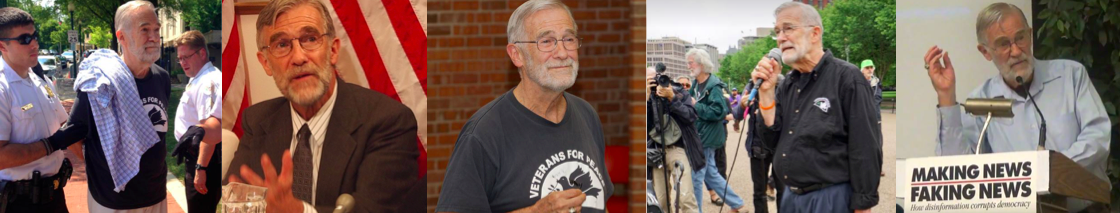

Ralph W. McGehee, a veteran of the Central Intelligence Agency’s clandestine crusades in Vietnam who went to war against the C.I.A. itself, died May 2 at an assisted-living facility in Falmouth, Maine. He was 92. The cause was Covid-19, his son, Dan McGehee, said.

Mr. McGehee’s 1983 memoir, “Deadly Deceits,” was a scathing critique, a chronicle of the C.I.A.’s Cold War covert operations in Southeast Asia and his dawning realization that the American cause in Vietnam was doomed. He recalled his epiphany: At the end of 1968, he sat drinking alone in a sparsely furnished villa outside Saigon, listening to a tragic pop song, “The End of the World,” as helicopter gunships circled overhead and B-52s dropped bombs in the distance.

“My idealism, my patriotism, my ambition, my plans to be a good intelligence officer to help my country fight the Communist scourge — what the hell had happened?” he wrote. “Why did we have to bomb the people we were trying to save? Why were we napalming young children? Why did the C.I.A., my employer for 16 years, report lies instead of the truth?” He struggled to answer those questions for the rest of his life.

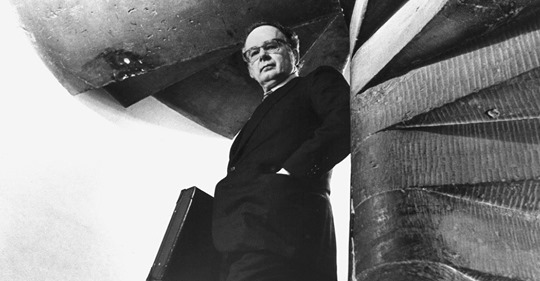

After growing up on the South Side of Chicago, starring on Notre Dame’s undefeated college football teams from 1946 to 1949, failing a tryout with the Green Bay Packers, and working as a management trainee at Montgomery Ward, he received a telegram from out of the blue in January 1952. It asked: Would you like to serve your country in an unusual way? Football players, given their brawn and affinity for teamwork, were prime candidates for paramilitary missions, in the eyes of the C.I.A.

The Korean War was at its height and the C.I.A., founded in 1947, was expanding exponentially, from 200 officers in the beginning to roughly 15,000 in 1952, with some 50 overseas stations and a budget exceeding $5 billion in today’s money. The agency searched frantically for Americans capable of conducting covert operations overseas.

Mr. McGehee made the grade. After training and indoctrination, the agency sent him out into the world. Serving over the years in Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand and South Vietnam, he confronted confounding problems: for example, a richly compensated foreign agent from Taiwan whose highly touted secret reports on Communist China were based on nothing but newspaper clippings. In northern Thailand, he worked on counterinsurgency operations with opium-smoking hill tribesmen, to little avail. He tried, with some success, to train the Thai national police to gather intelligence.

Mr. McGehee rose to the very middle of the C.I.A.’s ranks, and in 1968 he landed in Saigon to work in liaison with the chief of the secret police. He then faced a spiritual crisis. The war was going badly for the United States, and as bad turned to worse, it shattered him. He questioned America’s role in the world, the C.I.A.’s role in Vietnam, his role in the C.I.A., and his very existence. He wrote that he had contemplated unfurling a banner reading “THE C.I.A. LIES” and then killing himself to protest the war.

As a football star at Notre Dame, Mr. McGehee had the kind of talent the C.I.A. was looking for. By 1973, after he returned to headquarters, labeled a malcontent and relegated to a backwater desk, the agency confronted its own existential crisis. The wars of Watergate would breach the ramparts of its secrecy. Cold War skeletons tumbled from the closet: assassination plots, covert support for autocrats, spying on Americans. Presidents had approved such exploits in secret, but the C.I.A. was blamed and shamed. By the time he retired in 1977, Mr. McGehee was convinced that the agency was a malevolent force.

“Deadly Deceits: My 25 Years in the C.I.A.” appeared six years later, after the agency had sought and won significant deletions. Though C.I.A. veterans had published memoirs since the 1960s, few had accused the agency of distorting intelligence to deceive American presidents and the American public to protect its power.

“The American people are the primary target audience of its lies,” Mr. McGehee wrote. Now-declassified Cold War records tell a more complicated story. The C.I.A.’s primary audience was presidents, not the public. Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon had rejected the C.I.A.’s pessimistic reporting on Vietnam, telling the American people that victory, or peace with honor, was at hand when it wasn’t. The presidents, their national security advisers and the Pentagon had pressured the C.I.A. to confirm their political preconceptions. Sometimes the agency bent to their will, but not often.

Those records do bear out Mr. McGehee’s critique that the C.I.A. had neglected the gathering and analysis of intelligence, its founding mission, in favor of bold covert operations that changed the world, often for the worse, especially in the years leading up to the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, approved by President John F. Kennedy, in 1961.

Ralph Walter McGehee Jr. was born in Moline, Ill., on April 9, 1928. His parents managed an apartment complex, his mother as a bookkeeper and his father as a maintenance man.

His wife of 63 years, Norma (Galbreath) McGehee, died in 2012. In addition to his son Dan (who is also known as Keenan Dakota), his survivors include another son, Scott; two daughters, Jean Marteski and Peggy McGehee Horton; 10 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

In later years Mr. McGehee developed and maintained CIABASE, an online collection of open-source information, and gave lectures, occasionally laced with conspiracy theories. He once told a reporter for The New York Times that he realized that his book would not change the C.I.A. But, he said, “I guess I justify myself by thinking that I fought for what I thought was right.”