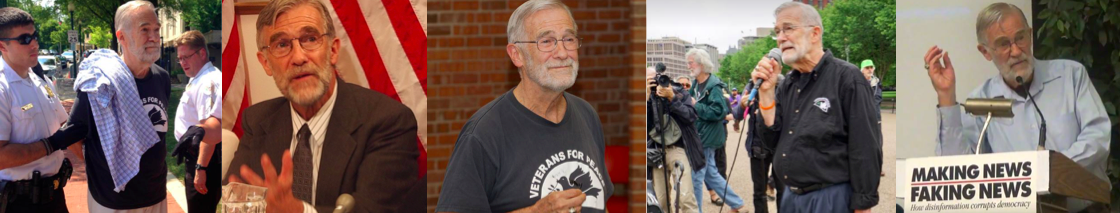

By Ray McGovern, May 22, 2023

The automatic response usually is, “Yes, he certainly had options other than invasion and he should have chosen one of them first”.

This assumption bespeaks the poverty of the discussion on Ukraine. The corporate media is, of course, largely to blame. But others, too, have not taken a hard look at whether the facts support that kind of facile answer. And so, not only has it become holey – yes, holey – dogma; it may get us all killed.

The facile response sits atop a fallacious syllogism that bodes high danger, particularly at this key juncture when misled citizens may acquiesce, yet again, to further escalation in Ukraine. The syllogism:

The Russians had other options to invading Ukraine.

They attacked Ukraine in a ‘war of choice’; also threaten NATO.

Ergo, the West must arm Ukraine to the teeth, risking wider war.

The unexamined major premise lurks in every corner, including in very timely and instructive statements like the one the NY Times published on May 16. (https://eisenhowermedianetwork.org/russia-ukraine-war-peace/). It said:

Our attempt at understanding the Russian perspective on their war does not endorse the invasion and occupation, nor does it imply the Russians had no other option but this war. Yet, just as Russian had other options, so did the U.S. and NATO leading up to this moment.

The attempt at balance – however transparent – is welcome. But are readers not owed some attempt to spell out those “other options”? This is not a marginal quibble; we are talking war. When one glibly asserts, glibly, that that a country that launched hostilities had other options, well, what were they? A statement as lengthy as that published in the NYT might have made room for an attempt to cite one or two of those options (This lacuna was why I demurred when asked to sign the ad.)

Please do not misunderstand. I think that, on balance, the NYT ad was pure gift to those who will be educated by it (and something of a miracle that the Times published it). Besides, I know the crafters and the signers of that statement well enough to rule out any thought that the omission might be attributed to fear of being seen to be in ‘Putin’s pocket’. Likewise, these are not the kind of folks to massage words to ensure political correctness.

Rather, it seems to me likely a case of accepting the ‘received wisdom’ that surely Putin had other options, without thinking that key question through carefully – not fully realizing how important it is to be more fully informative. Especially now.

A Harsher View

Professor Oliver Boyd-Barrett is more harsh – too harsh, in my view – in his criticism of the NYT full-page ad. He gives an approving nod to its call for an adult-type recognition that opponents also have legitimate interests. But he adds that the statement “immediately stumbles at the first gate, namely, by blaming Russia for its Special Military Operation (SMO) in Ukraine”. He attributes this to “an inability to dig behind cliché superficiality”.

Boyd-Barrett: “Putin launched the SMO precisely because he was intelligent enough to confront and defy the reality that the west was relentlessly working towards just such a conflict and that, as Machiavelli once observed, the longer he refrained from acting then the more disadvantageous his ultimate military plight”. https://oliverboydbarrett.substack.com/

Watching What Leaders Say

As a Kremlinologist for half a century I have some insight into what experienced practitioners can glean from media analysis. Historians are usually the best of them. Since media analysts are a vanishing species, I was encouraged to find a thoughtful piece on Ukraine by Geoffrey Roberts, Emeritus Professor of History at University College Cork, Ireland.

Below are short excerpts from an analysis he called, ‘Now or Never’: The Immediate Origins of Putin’s Preventative War on Ukraine (published last December in Journal of Military and Strategic Studies): https://jmss.org/article/view/76584/56335

Humans are the cause of all their own actions, not least in precipitating war. Such actions may be irrational, incoherent or overly emotional, but they remain intelligible and re-presentable in an explanatory narrative of what happened and why. This narrative approach … is empirically driven. It relies on … evidence that enables us to figure out … agent motivations and calculations.

This essay is devoted to the when and why of President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine in February 2022. … It relies almost entirely on the record of Putin’s public pronouncements during the immediate prewar crisis. … What this evidence shows is that Putin went to war to prevent Ukraine from becoming an ever-stronger and threatening NATO bridgehead on Russia’s borders. …

The longer war was delayed, he argued in February 2022, the greater would be the danger and the more costly a future conflict between Russia, Ukraine, and the West. Better to go to war now …

Roberts also pointed out that on Dec. 21, 2022, Putin told Russian military leaders it was “extremely alarming that elements of the US global defense system are being deployed near Russia…If this infrastructure continues to move forward, and if US and NATO military systems are deployed in Ukraine, their flight time to Moscow will be only 7-10 minutes, or even five minutes for hypersonic systems.”

Was Putin Blowing Smoke?

Media analysis joined with those with expertise in more technical areas, can be a huge help to policy makers, congress members – to anyone interested in the facts. I, too, had taken note of what Putin told his military at that critical juncture in late December 2021. I enjoy a huge advantage in being able to consult serious, reliable specialists, among them Ted Postol, professor emeritus (MIT) in physics and former top adviser to the Chief of Naval Operations.

I invite you to view what came out of that collaboration:

No, Putin was not just blowing smoke. Ted and I could demonstrate that U.S. missile emplacements in Romania and Poland were a legitimate concern to Russian leaders; that Putin’s time-to-target information was not exaggerated; and that the analogy we drew with the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 was a helpful way to illustrate that Kremlin concerns were not synthetic, but real.