Dare to Appease: Finnish Lessons for Ukrainian Peacemakers

What Ukraine could learn from Finland’s war with the Soviet Union

By Geoffrey Roberts, August 29, 2025

The oft-cited analogy drawn between the Russo-Ukrainian war and the Soviet-Finnish wars of the 1940s is not as simple as it may seem. Indeed, the differences between the two sets of events are certainly as significant as any similarities. By no means are Kiev’s situation and choices the same as those faced by Helsinki 80 years ago. Nevertheless, the parallels between the Finnish and Ukrainian struggles to survive as independent states remain striking and instructive.

Of all the lessons of Finnish-Soviet relations for present-day Ukraine, the most pertinent is that having twice brought their country close to catastrophe, Finland’s leaders had the courage to accept defeat, thereby saving their state’s sovereignty and independence. Moreover, it was Finland’s postwar appeasement of the Soviets that effectively safeguarded the country’s future as well as providing a basis for the stability and prosperity that has made it one of Europe’s most successful nations.

Like the Ukraine war, the so-called ‘Winter War’ of 1939-1940 was entirely avoidable. Stalin preferred a diplomatic solution to resolve his security concerns, as did Putin in 2022. It was the failure of diplomacy that led to the Red Army’s invasion of Finland in December 1939.

Finland, together with Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, was part of a Baltic sphere of influence gifted to Stalin by Hitler under the auspices of the Nazi-Soviet pact. Stalin aimed to draw all four Baltic countries into his orbit by means of mutual assistance pacts and Soviet military bases. But in relation to Finland, he made a significant additional demand – that the Finns should concede their southern Karelian Isthmus territory bordering Leningrad, which Stalin considered vital to safeguard the security of the Soviet Union’s second city.

While the Baltics capitulated to Soviet threats and demands quite quickly, the Finns recoiled. Stalin’s response was to drop his demand for a mutual defence pact but he insisted on major territorial concessions, while also offering to transfer a big chunk of Soviet Karelia to Finland.

Finnish Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim, himself a former Tsarist general, warned that war with Russia would be a disaster for Finland. But his political masters, believing their hand to be stronger than it actually was, underestimated Stalin’s determination to secure the Soviet position in the Baltic.

His deal refused, Stalin launched military action, calculating that a quick and easy war would soon lead to regime-change in Helsinki.

Contrary to propaganda myths, plucky Finland did not fight the Soviets to a standstill during the ‘Winter War’. Heroic Finnish defenders did prevent an immediate Red Army breakthrough and inflicted heavy casualties, but the Soviets re-grouped and launched a second offensive in January 1940. By early March the Red Army was poised to capture Helsinki and occupy the whole of Finland. Wisely, the Finns sued for peace and secured a treaty whose terms were not so different from what had been on offer before the war.

Finland had indeed asserted its independence – at the cost tens of thousands of dead fighters. Soviet casualties were higher still, but the 5-million strong Red Army was well able to absorb such losses.

In agreeing to what was, in effect, a compromise peace, Stalin was mindful of the impending arrival in Finland of an Anglo-French expeditionary force – ‘volunteers’ supposedly tasked to aid the Finns, but actually intent on seizing control of Sweden’s iron ore fields – a vital resource of Germany’s war economy.

As the British historian, A.J.P. Taylor commented: “The British and French governments had taken leave of their senses.” Their actions threatened to spread the European war north to Scandinavia – a prospect that neither Stalin nor the Swedes nor the Finns, wanted – effectively pushing the Soviets even deeper into the German orbit.

The Soviet-Finnish peace treaty saved Sweden’s neutrality, but came too late for Denmark and Norway – invaded by the Germans in April 1940 precisely in order to protect the transhipment of essential Swedish iron ore.

Sweden remained neutral for the rest of war, but Finland’s leaders chose to join the June 1941 Nazi attack on the USSR. The Finns called their second engagement with the Soviets a ‘Continuation War’ and claimed they were not Hitler’s allies but were co-belligerents, whose aim was to retrieve lost territory. For the Soviets, the Finns’ rationale was a distinction without difference, given the extent of Finland’s military collaboration with Germany and its role in sealing the blockade of Leningrad – a siege that cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Soviet civilians.

When the Red Army finally broke through Finnish defences in summer 1944, Finland faced another momentous choice: agree to Soviet terms for an armistice or continue to fight alongside Germany to the bitter end.

Finland’s decision in September 1944 to accept armistice and defeat averted a Soviet occupation and curtailed the needless destruction wrought by a war that had cost 100,000 Finnish lives. It was a desperate decision but, as Finnish historian, Kimmo Rentola, highlights in his book How Finland Survived Stalin (Yale University Press 2023), it was born of strength as well as weakness. The Finns had shown their mettle in two wars with the Soviets. They had suffered significant territorial and human losses but the core of their country remained under Helsinki’s control. Finland’s political institutions and societal structures remained intact. Its national unity was battered but not broken and the Finnish government retained its coherence and decision-making power.

The Soviet armistice terms were harsh but not overly onerous: additional territorial losses in the area of Salla and Petsamo, a naval base on the Porkkala peninsula south of Helsinki (which the Soviets gave back in 1956), US$300 million of reparations, a ban on fascist organisations, punishment of war criminals and legalisation of the communist party. The Finns were also required to break all links with Germany and forcibly expel German forces from their soil.

In the circumstances, it could certainly have been a lot worse. As a character in Väinö Linna’s great Finnish war novel – The Unknown Soldier – said: “The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics won, but persistent little Finland crossed the line a respectable second”.

Of all the enemy states defeated by the Red Army during World War II, Finland was the only one to remain unoccupied. However, the Finnish communist party was among Europe’s strongest – winning a quarter of the popular vote in the 1945 elections – and the danger of a Soviet-sponsored seizure of power persisted.

That threat was lifted by the signing in 1948 of the Finnish-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Security – the pact that framed Finland’s relationship with the Soviet Union during the cold war as a both a buffer and a bridging state. Helsinki pledged to defend Moscow’s northern flank but was otherwise free to pursue an independent, non-aligned foreign policy. Nor did the Soviets object to a militarily strong Finland, as long as its ‘armed neutrality’ was not directed against them. On the domestic front, the Finns continued to manage their own affairs, including the removal in July 1948 of the communists from the coalition government that had hitherto ruled postwar Finland.

A key architect of the policy that came to be labelled ‘Finlandisation’ was Urho Kekkonen, Finland’s prime minister and president for much of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Kekkonen’s maxim was that the more the Soviets trusted Finland the greater its freedom in foreign as well as domestic affairs. His crowning achievement was hosting the 1975 Helsinki Conference on Security and Co-operation Europe – the pinnacle of East-West détente during the first cold war.

Kekkonen’s relations with his Soviet interlocuters bordered on the intimate. No foreign leader was treated with more respect and deference by the Soviets, not even the heads of other communist states.

Ukraine has already suffered more damage than was inflicted on most countries during the entire Second World War, including Finland. It has lost 20% of its territory. Its society is battered, bruised and divided, its internal political cohesion teetering on the brink of collapse. But it remains a functioning state, whose government continues to control the country’s central territorial core. No one doubts the courage and resilience of Ukraine’s armed forces. Unlike Finland in the 1940s, Ukraine has strong international backers and the potential for rapid postwar recovery.

It is not too late for Ukraine’s leaders to take the momentous and brave decision to cross the line ‘a respectable second.’

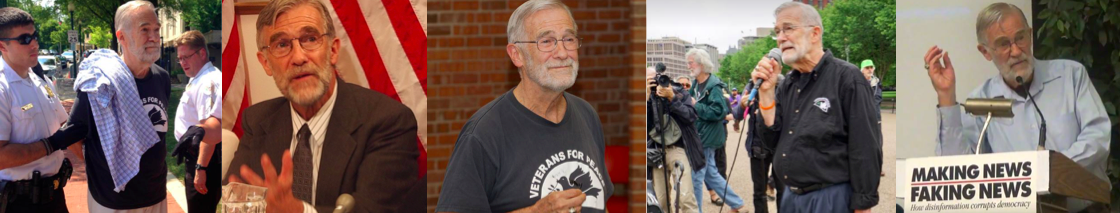

Geoffrey Roberts is Emeritus Professor of History at University College Cork and a member of the Royal Irish Academy.